Will the new German government decide to split the single bidding zone?

Written by Christoph Maurer

Recognisable movement

Auszug aus dem Ergebnispapier der AG Klima und Energie der Koalitionsver-handlungen zwischen CDU/CSU und SPD 2025 (Quelle: AG Klima und Energie, 2025)

The interim results of the working group on climate and energy from the German coalition ne- gotiations between the centre-right CDU/CSU and centre-left SPD are now available. In one re- spect, they are really hopeful. For the first time, a major party, the SPD, has shown a willingness to consider an amendementof the German electricity bidding zone.

Questioning long-held positions that have been vehemently defended by politicians, industry and trade unions demonstrates strategic foresight and an understanding that the energy transition is indeed entering a new phase. The next step is now to convince the CDU and CSU. For this reason, the following summarises the main arguments in favour of a bidding structure and outlines possible solutions to widely suspected problems.

Broad scientific consensus

The bidding zone debate differs from many other debates surrounding the organisation of the energy system and the design of the electricity market. While scientists disagree on many energy market related issues and often argue along fundamental economic policy preferences, there is a very broad consensus on the question of whether the single bidding zone makes economic sense or should rather be divided. In the summer of 2024, this became clear in a joint opinion piece by twelve energy economists in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (Hirth et al., 2024) .

The recently published status update of the Expert Commission (Löschel et al., 2025) on the status of the energy transition also clearly recommends bidding zone separation, as do several of the scientific articles in the March issue of ifo schnelldienst (Grimm et al., 2025) , which deal specifically with the issue of electricity market design.

What are the economic consequences of keeping the single bidding zone?

Without a bidding zone amendment, three major problems will arise in the coming years that will jeopardise the efficiency of the German electricity market:

- Demand-side flexibility and storage systems do not receive any meaningful dispatch signals. Storage facilities in the south will potentially charge when prices are low due to high wind, even though the wind power does not reach them. Storage facilities in the north, on the other hand, might discharge at higher prices (e.g. in high-load, high-wind situations) despite north-south bottlenecks. Congestion will increase in both situations. It is foreseeable that many battery storage systems will be added in the coming years. Without locational prices, we are giving away their potential for reducing congestion, as this potential cannot be meaningfully integrated into the cost-based redispatch process.

- Interconnectors are used inefficiently. Because the Germany-wide price signal does not reflect the bottlenecks, we will import electricity from Scandinavia while we have to curtail wind power in the north. And we will export electricity to our southern neighbors even though we cannot physically deliver it to the interconnections. To remedy this and maintain system security, we need expensive grid reserves from power plants that have actually long since reached the end of their useful lifetime. And in a future power plant strategy or capacity market, we must hope that the European Commission will agree to a local component in the state aid notification procedure, which is anything but a given. With a split bidding zone, on the other hand, it would be clear that requirements would have to be determined and procured regionally.

- The expansion of renewable energy also increases the forecast errors that occur shortly before delivery. If the RE producers balance these via Germany-wide intraday trading, new bottlenecks that are critical for system security can arise shortly before operation (up to 5 minutes). This is because redispatch, which is used to correct existing congestion after electricity trading, is complex to coordinate and takes time. Additional redispatch cannot be organised in five or even 30 minutes. In the worst case scenario, there is a risk of n-1 security being breached

The transmission system operator Amprion described the latter risk in particular at the end of last year in an expert article in Energiewirtschaftliche Tagesfragen (Sapp et al., 2024) . The article also hints at what threatens without efficient price signals that at least limit the emergence of short-term bottlenecks. Among other things, so-called feasibility ranges are discussed, in which the TSOs would have to limit the flexibility of power plants, for example, but also of renewable energy plants and storage facilities, preventively, i.e. even before trading and without knowing the bids of a plant.

The alternative to efficient prices is therefore not the status quo with flexible Germany-wide intraday trading with gate closure almost immediately before delivery. Instead, many players are threatened with the loss of trading opportunities on the short-term electricity market because this could jeopardise system security. This means a loss of revenue and thus reduced investment incentives, e.g. for storage facilities, and at the same time welfare losses for us all.

Must there be losers?

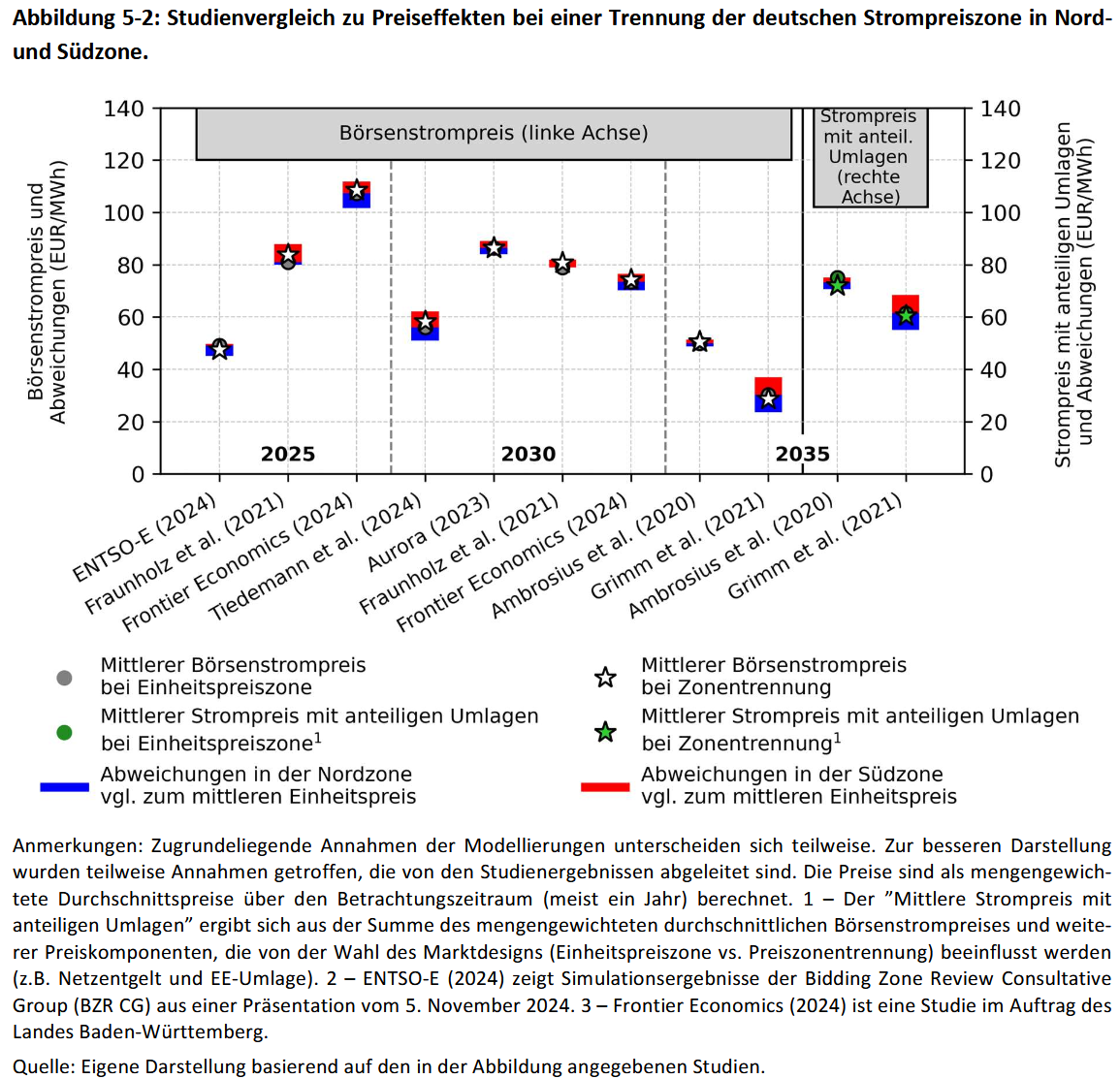

Studienvergleich zu Preiseffekten der Expertenkommission zum Monitoring der Energiewende (Quelle: Löschel et al., 2025, S. 15)

When wholesale prices change, there can be winners and losers. In view of the generally high energy prices, the fear of price increases, particularly for consumers in the highly-industrialized states (Länder) in the south and west with a high proportion of industry, is a key driver for the resistance of politics and business to a zone division

However, it is often forgotten that a bidding zone amendment is not a zero-sum game. Instead, it would reduce the costs of the electricity system as a whole and achieve welfare gains. In particular, transmission fees would fall due to lower redispatch costs, without any subsidy having to be paid from the budget (which is currently under discussion). Grid costs would also be lower in the long term because the need to expand the grid would be reduced if the zones were divided.

In addition, the average wholesale price effect is often overestimated. In most of the studies that have been carried out in recent years, the annual average is less than €ct1/kWh. This is also shown by an analysis from the status report of the Expert Commission for Monitoring the Energy Transition.

This is because the main effect of a bidding zone reconfiguration is not a uniform price increase in one zone compared to the other. Rather, the splitting of the single German bidding zone means that prices can differ in individual hours in order to reflect congestion in the grid. When there is strong wind, the prices in the northern zone are lower than in the southern zone; when there is a high PV feed-in in the south, it can be the other way round.

And finally: Remaining effects for those who would actually be severely affected by the price changes, in particular the industrial sectors with a high dependency on electricity prices, can and should be compensted. This can be done without jeopardising the essential benefits of price zone separation

The basic idea of such compensation is that an affected consumer, e.g. an industrial company in the south, receives a credit at the end of the year, amounting toof its own electricity consumption times the average annual price difference between its zone and the reference price of a single bidding zone.[1] This compensation offsets any additional costs caused by a locally higher wholesale price. At the same time, the compensated consumer, like all other consumers, benefits from the additional reduction in grid charges. As the compensation is based on average annual price differences, the price differences in individual hours, which are relevant for dispatch decisions and may be much higher in individual hours, remain visible and relevant for the market participants and ensure efficient incentives and congestion avoidance.

At the same time, no external financing is required for this compensation. It can be financed from the congestion income accruing at the new bidding-zone border. Such congestion income always arises when the prices between two zones actually differ, i.e. when there is a need for compensation. Compensation for such significant market design changes is also not without precedent. In markets in the north-east of the USA, for example, which have already moved towards more localised price signals some time ago, they have been used to resolve the associated distribution conflicts (Kunz et al., 2016) .

[1] Various design issues arise, for example, with regard to the question of whether the electricity consumption used for offsetting is determined on the basis of actual consumption or historical data and which zone price is used for offsetting (hypothetical prices of a continued uniform bidding zone or, for example, the price of the northern zone).

Summary

For the first time, political players are prepared to consider splitting the single German bidding zone. This is a huge opportunity because the status quo is not sustainable in the current form. Without efficient price signals, we are not only giving away the potential of flexible consumers and storage systems to relieve the grids and therefore must expand grids more than necessary. There is also the threat of system security problems in the future, which cannot be resolved with redispatch as has been the case to date.

We should therefore seize the opportunity to fundamentally reduce the costs of the electricity system by amending the bidding zone configuration. This would also make it possible to compensate those initially negatively affected by such a step in an incentive-preserving manner and thus advance the energy transition for all.

Article for downloadReferences

AG Klima und Energie (2025), Koalitionsverhandlungen CDU/CSU/SPD AG 15 – Klima und Energie. FragDenStaat. https://fragdenstaat.de/dokumente/258015-koalitionsverhandlungen-cdu-csu-spd-ag-15-klima-und-energie/. Zugegriffen: 27. März 2025.

Grimm, V., Ockenfels, A., Hirth, L. et al. (2025), Strommarkt – Balance zwischen Wettbewerbsfähigkeit, Nachhaltigkeit und Bezahlbarkeit. ifo schnelldienst 78, Nr. 3: 3–35.

Hirth, L., Ockenfels, A., Bichler, M. et al. (2024), Der deutsche Strommarkt braucht lokale Preise. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 10. Juli 2024. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/klima-nachhaltigkeit/der-deutsche-strommarkt-braucht-lokale-preise-19845012.html.

Kunz, F., Neuhoff, K. und Rosellón, J. (2016), FTR allocations to ease transition to nodal pricing: An application to the German power system. Energy Economics 60: 176–185.

Löschel, A., Grimm, V., Matthes, F. und Weidlich, A. (2025), Statusupdate zum Stand der Energiewende. Expertenkommission zum Energiewende-Monitoring. Berlin. https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Energie/statusupdate-zum-stand-der-energiewende.html. Zugegriffen: 26. März 2025.

Sapp, F., Maaz, A., Peters, A. und Flinkerbusch, K. (2024), Zurück zur Physik – Wege zur Zusammenführung von Stromhandel und Netzbetrieb. Energiewirtschaftliche Tagesfragen 74. Jahrgang, Nr. 9: 22–27.